Heat Transfer In Pipes - Detailed Discussion

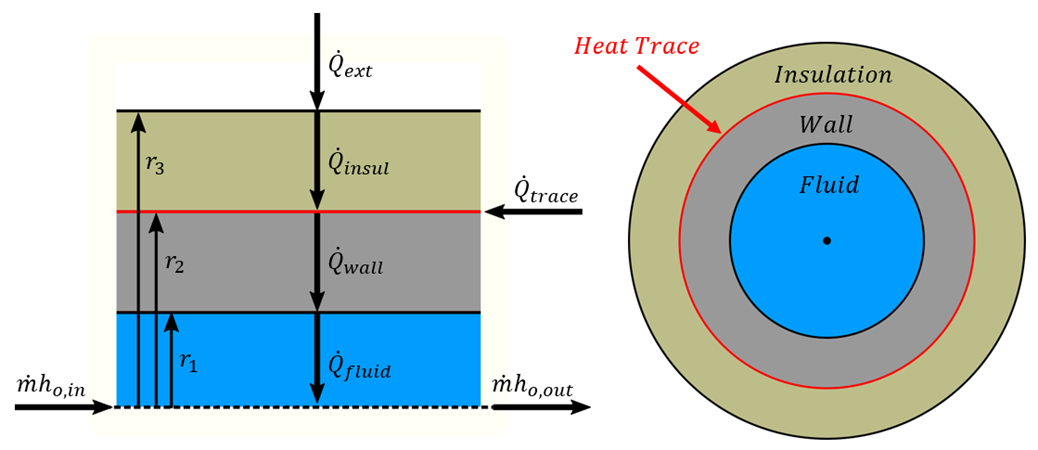

Figure 1 - Diagram of a pipe with Heat Tracing and Insulation

There are many possible combinations of heat transfer that can be defined in AFT Arrow. In any of these models there are various heat flows that can be considered.

Figure 1 shows the heat rates for one of the more complex cases – convective heating with a heat trace on the outer face of the pipe wall. Because this is a steady-state problem, any control volume that is drawn around sub-sections or the entire section must have entering heat equal to leaving heat.

Balancing these heat rates and temperatures via iterative methods allows AFT Arrow to come to a unique solution.

Heat Rates

As a hydraulic solver, the primary heat rate of interest is

, the heat added to the fluid itself. Adding heat to the fluid has the effect of raising its temperature.

, the heat added to the fluid itself. Adding heat to the fluid has the effect of raising its temperature.

We can derive an expression for

with the first law of thermodynamics. For convenience, we use specific quantities (per unit mass)

with the first law of thermodynamics. For convenience, we use specific quantities (per unit mass)

The energy e is composed of internal energy u and kinetic energy V2/2. Note that the gravity term gz is neglected from this equation to simplify the derivation.

The work done by the fluid is comprised of pressure work pv and shaft work wshaft

Combining and rearranging

Using the definition of enthalpy

In this analysis, we consider that the velocity through the control volume remains constant. In reality, changing temperature will cause the density of the fluid to change, and thus the velocity. For this reason, pipes in AFT Arrow are thermally sectioned. This means that certain properties are considered constant throughout the section as an approximation – having several sections in a pipe helps increase the accuracy of this approximation.

There is also no shaft work being done on the fluid.

We further assume that this can be treated thermodynamically as a constant pressure process. That is, cp is constant in the thermal section, like density. With this assumption we can use the relationship

To find that

Rather than using specific quantities, it is useful to relate heat rate and mass flow. Multiply both sides by ṁ

The other heat rates in the system can be related to

and other user defined values like

and other user defined values like

or

or

by examining various control volumes and surfaces:

by examining various control volumes and surfaces:

We now have a system of equations that allow us to determine all the heat rates in the system given a mass flow (determined from a mass balance), a specific heat (defined versus temperature) and a change in temperature. However, we do not know what this change in temperature is. To find it, we need to relate the surface temperatures to the heat rates.

Surface Temperatures and Resistance

Thermal resistances are useful because they directly relate the heat rate between two points with the temperature between those points.

The value of resistance depends on the mechanism of heat transfer

For conduction, the area and thus resistance changes with increasing r, so an integration must be done

These resistances can all be calculated with user-defined data. AFT Arrow helps simplify this by offering several correlations that can be used to determine the heat transfer coefficients in the above equations from more readily available parameters.

With resistances and

![]() , all the surface temperatures can be determined. By bounding the system with a given Tambient we can work outside in to find the required Tfluid to obtain those heat rates.

, all the surface temperatures can be determined. By bounding the system with a given Tambient we can work outside in to find the required Tfluid to obtain those heat rates.

If the result for Tfluid matches the values used for ΔTfluid used for determining

![]() , the correct solution has been found. If they are different, ΔTfluid needs to be adjusted and the process repeated until reaching a stable solution.

, the correct solution has been found. If they are different, ΔTfluid needs to be adjusted and the process repeated until reaching a stable solution.

Overall Heat Transfer

Wherever there are sequential thermal losses, it is convenient to combine these losses. This is straightforward:

Additionally, an overall heat transfer coefficient U can be defined which behaves similarly to h or k

Using the heat rate and resistance relationship, as well as the fact the heat transfer is into the fluid

Transforming the equation into a differential form on radius and length

Rearranging and integrating

We arrive at an expression relating the temperature change along the pipe and temperature change through the pipe:

Thermal resistances depend on the conduction and convection coefficients k and h which can be directly specified or calculated via a correlation.

The convection coefficient for internal fluid convection can be calculated with the Gnielinski Correlation or the Dittus-Boelter Correlation which can be seen in Incropera. These correlations determine the Nusselt number of the fluid – a ratio of convective to conductive heat transfer. Conductive properties are required input – with a Nusselt number and conductivity defined, the convection coefficient can be calculated.

These correlations also make use of the Prandtl number, a ratio of viscous diffusion to thermal diffusion.

Gnielinski

Dittus-Boelter

External convection behavior differs from the above. AFT Arrow provides the Churchill-Bernstein correlation for determining a convection coefficient from ambient temperature and fluid velocity. This correlation can be used for pipes over which boundary layers develop freely, free of constraints imposed by other surfaces. All of the external fluid properties are evaluated at the film temperature.

Buried Pipe Heat Transfer

Buried Pipe heat transfer is modeled by solving directly for the thermal resistance of the soil layer. AFT Arrow uses a model developed by Eckert and DrakeEckert, E.R.G., and Drake, R., Analysis of Heat and Mass Transfer, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 1972. to directly calculate the thermal resistance of soil on top of a pipe for use in the overall thermal resistance network:

In this model, z is the distance between the ground surface and the pipe center-line, while r is the outside radius of the pipe.

Related Topics

Related Blogs

Let the Heat Flow: Modeling Heat Transfer in Pipes in AFT Fathom and AFT Arrow