Role of Pressure Junctions - Detailed Discussion (Long)

In modeling a generalized pipe network, it is possible to construct models that do not have a unique solution. A common occurrence of this is when a model contains one or more sections which are completely bounded by known flow rates. A series of examples with accompanying explanation will clarify situations where this occurs. The length of this topic is proportional to the frequency with which engineers get confused over the issue. It became apparent that an exhaustive, lengthy discussion was necessary for some engineers. Do not dismiss this topic too quickly because of its length.

Before beginning it will be helpful to consider an aspect of the philosophy of computer modeling. At the risk of stating the obvious, it must be recognized by the user that a computer model cannot calculate anything that cannot in principle be calculated by hand. All the computer does is accelerate the calculation process. Some users expect the model to generate independent information and become frustrated when the software requests additional information from them. But if the user was doing the calculation by hand that same information would still be required. The difference is that in the case of the hand calculation, the engineer would be forced to think through why the information is needed.

However, when the engineer interacts with AFT Impulse, they do not need to think at the same depth as in the hand calculation. So when AFT Impulse asks for the additional information, it is not as apparent why it is required. This disconnect in thinking can cause frustration for the user. Fully understanding the concepts in this topic will greatly reduce the frustration for some users, and will improve the quality of models for all users.

Examples

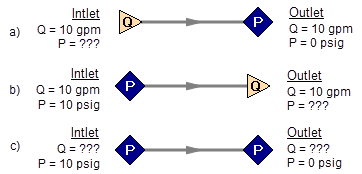

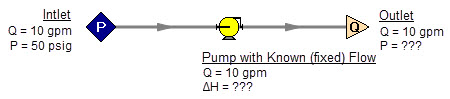

The simplest example is the system shown in Figure 1. In AFT Impulse terms, the system has two assigned flow junctions.

Figure 1: Model with two assigned flows. This model does not have a unique solution.

Obviously, the flow in the pipe is known. But what is the pressure at the inlet? At the outlet? It cannot be determined because there is no reference pressure. The reference pressure is that pressure from which other pressures in the system are derived. There can be one or more reference pressures, but there always has to be at least one.

The model in Figure 1 can be built with AFT Impulse and if you try and run this model, AFT Impulse will inform you that it cannot run it because of the lack of a reference pressure. In AFT Impulse there are nine junctions that can act as a reference pressure: the reservoir, assigned pressure, spray discharge, pump with submerged option, and valve and relief valve after cracking (with the exit valve option) behave as reference pressures because that is their nature. Three other junction types, surge tank, gas accumulator, and assigned flow (when the steady-state flow is zero) have a special feature that allows them to act as reference pressures. This feature is found on each junction's Optional tab.

There are a couple other things worth noting about Figure 1. First is that the model in Figure 1 has redundant boundary conditions. When one flow is specified in a single pipe, the other end must have the same flow. Thus the second known flow does not offer any new information. Because the conditions are redundant, there is no unique solution to the model in Figure 1. In any AFT Impulse model, there is always at least one unknown for each junction in the model – either pressure or flow rate. Sometimes there are two unknowns such as a Pump. It is possible the user may not know either the flow or the pressure at the pump. In such cases the user is required to specify the relationship between flow and pressure. This relationship is called a pump curve, and by specifying the relationship between the two, effectively one of the two unknowns can be eliminated. Thus we always end up with one unknown for each junction.

Second, if the user was allowed to specify two flows as in Figure 1, they could specify them with different flow rates. Clearly they must have the same flow, so an inconsistency occurs. The basic reason the inconsistency is possible is because Figure 1 does not have a unique solution.

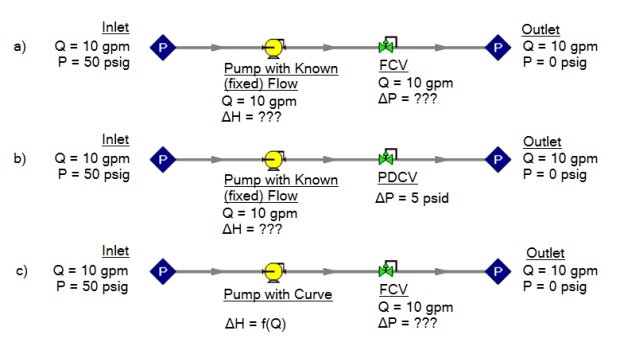

Figure 2 a-c shows three other model configuration possibilities. It is not possible to specify inconsistent conditions for any of the Figure 2 models, and they always have a unique solution no matter what input is specified by the user.

Figure 2: Top two models with one pressure and one assigned flow, bottom model with two pressures. All of these models have a unique solution.

The four models in Figures 1 and 2 a-c contain all logical possibilities. In all four cases there are four things we want to know. The pressure and flow at the inlet, and the pressure and flow in the outlet. In each case we know two of these four. The problem is that in the Figure 1 model the lack of a reference pressure makes it impossible to determine the inlet and outlet pressures, even though we know the flow. The three models in Figure 2 a-c all have at least one pressure and thus all four of the desired parameters can be determined. Table 1 summarizes this. Also note in Table 1 that in the Figure 2c case the flow can be determined, but it is by iteration.

Table 1: Four logical possibilities of boundary conditions for single pipe systems

| Case | Inlet Pressure | Inlet Flow | Outlet Pressure | Outlet Flow | OK? | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 1 | X | X | NO | No reference pressure, cannot calculate pressures | ||

| Figure 2a | X | X | YES | 1 known flow, can calculate everything directly | ||

| Figure 2b | X | X | YES | 1 known flow, can calculate everything directly | ||

| Figure 2c | X | X | YES | 2 pressures, can iterate for flow |

As we consider multi-pipe systems, there are a host of other possibilities that present themselves. All other configuration possibilities which lack a reference pressure ultimately boil down to the same problem that exists in Figure 1.

The pipe lengths, diameters and friction factors are not included in the remaining models because they do not influence the main point of this topic. It is assumed that these parameters can be obtained for each pipe and the resulting pressure drop calculated with standard relationships.

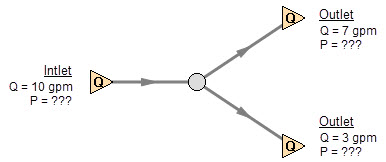

Consider the model in Figure 3. With three boundaries having a known flow, this clearly has the same problem as the model in Figure 1. No unique pressures at any location can be calculated.

A pressure at any one of the three boundaries in Figure 3 would be sufficient to allow a unique solution of the system. It is also possible that there could be two pressures and one flow, or three pressures. As long as there is one pressure a unique solution exists.

Figure 3: Three known flows at boundaries lack a reference pressure, similar to the model in Figure 1. This model does not have a unique solution.

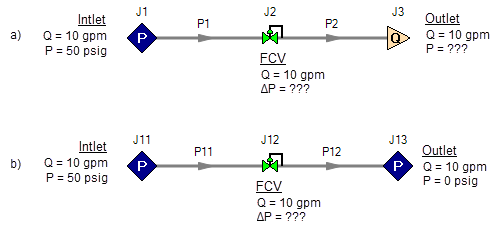

Now consider the models in Figure 4. The Figure 4a model does have one reference pressure, but in this case there is still a problem. The Flow Control Valve (FCV) is controlling the flow to 10 gpm, and the downstream flow is demanding 10 gpm. The section of the system before the FCV can be solved (because there is a pressure upstream), but the section after the FCV does not have a unique solution. Why? In order to obtain a unique solution, the pressure drop across the FCV must be known. But any pressure drop could exist and satisfy the conditions of this model. It is thus not possible to determine the pressure at the outlet flow demand because it depends on the FCV pressure drop which is not known. The model in 4b does have a pressure downstream of the FCV, and thus there is a unique pressure drop across the FCV and a unique solution exists for the model in Figure 4b.

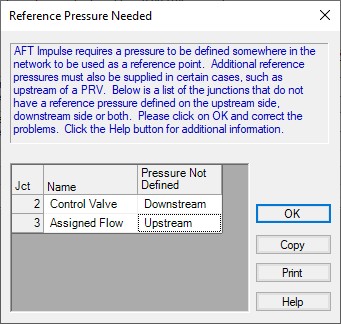

If you input the remaining data for the Figure 4a model and run it in AFT Impulse, you will get the message shown in Figure 5. AFT Impulse identifies the part(s) of the model where a known pressure is needed.

Figure 4a-b.: The model at the top does not have a reference pressure after the Flow Control Valve so the pressure drop across the FCV cannot be determined. The top model does not have a unique solution. The bottom model has a pressure upstream and downstream, and a unique solution exists.

Figure 5: AFT Impulse message when you try to run the model shown in Figure 4a.

Sizing Pumps with Flow Control Valves

An analogous situation to Figure 4a is when the user is trying to size a pump using the Pump with an assigned flow. The Pump with an assigned flow is really just a reverse FCV. It controls the flow by adding pressure, rather than reducing it. Figure 6 shows this case and is another example of a model without a unique solution, requiring more than one pressure junction. If the user instead entered a pump curve for this model, it could be solved.

Figure 6: A pump modeled as a fixed flow behaves identically to the FCV model in Figure 4a, for which no unique solution exists

Increasing in model complexity, Figure 7 shows some additional examples of models without a unique solution. In particular, Figure 7b has a pump with an assigned flow that can add as much pressure as it wants, and the downstream FCV can then take out as much as it wants. There are an infinite number of possible solutions.

While it would be highly unusual for a system to have two FCVs in series, it is worth considering the model in Figure 7b further. It is common to have an FCV in series with a pump. How does one size the pump in such a case? There are several ways to do this, one of which is to change the pump from an assigned flow to an actual pump curve. Trying multiple pump curves will guide you to the best pump.

But there is a better way. Consider for a moment the pressure drop across the FCV in Figure 7b. In the installed system, is any pressure drop acceptable? Usually not. It is typical to have pressure drop limits based on the system design and the FCV itself. A common requirement is a minimum pressure drop across the FCV. If no minimum pressure drop exists, let’s say we choose a pump that results in the pressure drop across the FCV being 0.01 psid. If the system is built and the pump slightly underperforms its published curve, the FCV will not be able to control to its flow control point. Even if the pump does operate exactly on the published curve, eventually fouling in the pipes will result in increased pipe resistance (and pressure drop) and again the FCV will not be able to control to its flow control point.

Figure 7: Neither model above has a unique solution. The top model has two flow control valves in series. The bottom model has a pump modeled as an assigned flow in series with an FCV. In both cases either a third pressure junction is needed between the two middle junctions, or one of the junctions must be changed from a flow controlling device.

To avoid these kinds of problems in installed systems, a minimum pressure drop across the FCV is typically required. This minimum pressure drop provides the key to sizing the pump in Figure 7b. Rather than model the FCV as a flow control valve, instead model it as a pressure drop control valve (PDCV) set to the minimum pressure drop requirement. Then a unique solution exists, the model will run and the pump can be sized. Once the pump is sized and an actual pump curve exists, the pump curve can be entered for the pump and the valve can be switched back to an FCV. Remember that when we use the PDCV, we are still getting the flow we want for the true FCV, because the pump is now providing the control.

Think for a moment what we just did. We went through a thought process that many engineers have gone through during their hand calculations. Specifically, we size the pump such that the FCV pressure drop is minimized. If the FCV has a larger pressure drop than the minimum, the pump must pump harder to overcome this excess pressure drop. In short, it must use more energy and is thus less efficient. Figure 8 depicts this process.

Figure 8a-c: The model at the top is the same as Figure 7b and does not have a unique solution. To size the pump, change the model to the second one shown above, which uses a pressure drop control valve (PDCV) rather than an FCV. Once the second model is run, the pump is sized, a pump curve exists, and the model at the bottom can be run using an FCV.

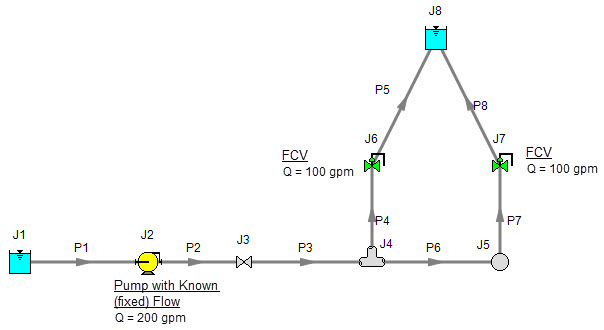

Let’s make a slight addition in complexity to the model in Figure 8. In this case we have two flow control valves in parallel (see Figure 9). To size this pump, we apply the process described in Figure 8. We choose one of the FCVs, make it a PDCV, size the pump, choose a pump with an actual pump curve and enter it into the model, then return the PDCV to an FCV.

Figure 9: A pump with an assigned flow in series with two parallel FCVs. The model in its current form does not have a unique solution. To size the pump, first change the FCV at J7 to a PDCV.

This brings up the question, which FCV should one choose to turn into a PDCV? When FCVs are put in parallel, frequently the pipe design has one of the FCVs further away from the pump that the others. Because of the additional piping leading to this FCV, it will be the weakest link in the chain of parallel FCVs by virtue of having the lowest pressure drop across it. The most remote FCV should be chosen as the PDCV. If the most remote FCV is chosen, when the minimum pressure drop required is applied to the PDCV all other FCVs in the parallel system will have greater than the minimum pressure drop - thus satisfying the pressure drop requirement for those FCVs as well.

What if you do not know which FCV is the most remote? In this case make your best guess, change it to a PDCV at the minimum required pressure drop, run the model, then verify whether all other FCVs have a pressure drop that meets or exceeds the requirement. If not, then the FCV with the smallest pressure drop as determined by the first run is in reality the weakest FCV. Choose this FCV, change it to a PDCV, and then change the original PDCV back to an FCV since it is not the weak link. If the pipe system leading to each FCV is truly identical and all FCVs have identical pressure drops, any of the FCVs will serve as the PDCV.

The preceding process can be extended to cases where there are three or more FCVs in parallel, and also cases with more than one pump in parallel supplying the FCVs.

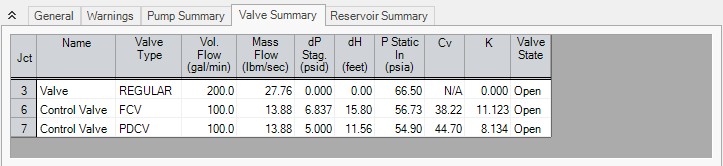

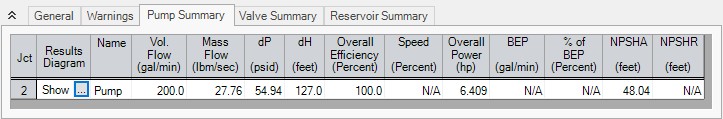

In Figure 9 the most remote valve is J7, the one on the right. If the minimum pressure drop is 5 psid, change J7 to a PDCV with a 5 psi drop. This results in the output shown in Figure 10a. Notice how the pressure drop across the other FCV at J6 (6.837 psid) is greater than 5 psid because it is closer to the pump. Also notice how the flow through J7 is still 100 pgm even though it is not controlling flow. Once again, the reason for this is that the pump is controlling the flow to 200 gpm, and with the J6 FCV controlling to 100 gpm, the excess must go through J7. The pump is thus sized and its pump pressure rise is shown in Figure 10b (113.5 ft.).

Figure 10a-b: Results from changing J7 in Figure 9 to pressure drop control valve

Pressure Control Valves

The problem of non-unique solutions can also occur when a Pressure Reducing Valve (PRV) or Pressure Sustaining Valve (PSV) is used. A PRV is used to control pressure downstream of the valve, while a PSV controls pressure at the valve inlet. One thing that PRVs and PSVs have in common with FCVs is that the pressure drop cannot be known ahead of time. The pressure drop depends on the balance of the pipe system.

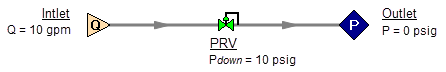

Consider the simple system shown in Figure 11. With the pressure controlled downstream of the PRV, the pressure upstream is not known. Without knowledge of the PRV's pressure drop, the pressure upstream of the PRV cannot be determined and thus no unique solution exists.

Figure 11: If a PRV is downstream of a known flow the PRV pressure drop cannot be calculated. This model does not have a unique solution.

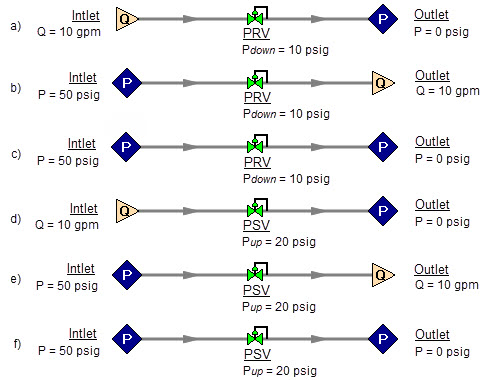

Figure 12 shows the possible cases with PRVs and PSVs, while Table 2 comments on the six cases. In summary, at least one known pressure is always needed on the side of a pressure control valve opposite of the controlled side.

Figure 12a-f.: Six possibilities for PRV and PSV configurations. Cases A and E do not have unique solutions. See Table 2 for comments.

Table 2: Summary of six possibilities for PRV and PSV configurations.

| Case | Inlet Pressure | Inlet Flow | Outlet Pressure | Outlet Flow | OK? | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 12a - PRV | X | X | NO | No reference pressure upstream of PRV, cannot calculate | ||

| Figure 12b - PRV | X | X | YES | 1 known flow, can calculate everything directly | ||

| Figure 12c - PRV | X | X | YES | 2 pressures, can iterate for flow | ||

| Figure 12d - PSV | X | X | X | YES | 1 known flow, can calculate everything directly | |

| Figure 12e - PSV | X | X | NO | No reference pressure downstream of PSV, cannot calculate | ||

| Figure 12f - PSV | X | X | YES | 2 pressures, can iterate for flow |

If a pump is being sized in series with a PRV or PSV, modeling the pump as an assigned flow will not permit a unique solution if the pump is upstream of a PRV or downstream of a PSV. The reasons for this are the same as those in the previous section on FCVs.

In combination with the previous examples, it should be apparent how the non-unique solution problem can occur in more complicated systems. In all such cases, the reasoning will boil down to the same problems already discussed.

Closing Parts of a System

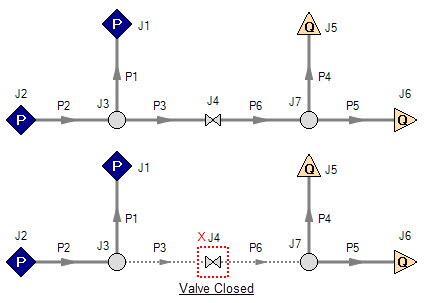

A model may be built which has sufficient information to obtain a unique solution. Then a user closes a junction and all of a sudden the problem of no unique solution occurs. This is shown in Figure 13. The top model has a unique solution and will run fine. In the bottom model the valve is turned off and the section of the system downstream of the valve has only known flows. No reference pressure exists in this section because it is isolated from the known pressures in the section on the left.

Figure 13: Top model has reference pressures at J1 and J2. Bottom model has closed valve at J4 which isolates the J5 and J6 assigned flows. There is no reference pressure for J5 and J6 and no unique solution exists for the bottom model.

There may be some situations - in particular for closed loop systems - where system components can act as a pressurizer and fix the pressure in the system during steady state when there is no flow. In this situation, it may not make sense to provide a reference pressure for the system using a traditional pressure junction. An example for this behavior would be a gas accumulator that pressurizes the system while there is no flow in steady state and then allow space to accommodate thermal expansion in the system.

In order to allow users to model that behavior, three different junctions have the ability to act as pressure reference points in steady state. These are the Assigned Flow junction, the Gas Accumulator junction, and the Surge Tank junction. The Properties Window pages for each of these junctions give a better description on how to properly define and use this feature.

For the Gas Accumulator and Surge Tank junctions, the ability to fix a zero-flow pressure is intended to allow users to better model a pressurizer component. During the transient simulation these junctions work to mitigate surge events by compressing or expanding the gas inside them as pressure waves travel through the system. During steady state, the initial conditions are fixed such that the pressure is a known, flow is zero, and the gas volume inside the junction is defined by the user as normal.

For the Assigned Flow junction, the ability to fix a zero-flow pressure is intended to allow users to model a situation where no flow is present in a pipeline and as a valve opens flow is introduced to the system. It is possible that during steady state, the reference pressure is known downstream of the closed valve, isolating the rest of the pipeline from a reference pressure. Defining this zero-flow reference pressure would allow the user to model a system that might not otherwise have a valid reference pressure.

It should be noted that while normal pressure junctions are typically capable of acting as an infinite fluid source, these three zero-flow reference pressure options will not. As the option implies, these features can only be used in a situation where zero flow is present. During the transient simulation, these junctions no longer act as reference pressures, do not have the potential to act as infinite fluid sources at constant pressure, and the pressure in the system is determined solely through the Method of Characteristics equations.

Summary

AFT Impulse models always require one reference pressure, and may require more if the engineer uses control valves, pumps with assigned flows, or closes pipes or junctions. The actual number of reference pressures needed depends on the model, but AFT Impulse always checks to be sure sufficient reference pressures exist and stops to warn the user when they do not.

This capability is a powerful diagnostic feature that will help guide the user in building meaningful models.